ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ACADEMY OF MARXISM CHINESE ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ABSTRACT

Somerville's brief critique of ecologically unequal exchange (EUE) theory illustrates how entangled traditional labour theories of value are in 19th century discourse on political economy. His incapacity to understand the point of EUE theory reflects the idealist myopia of such discourse, largely oblivious of the material metabolism of world society. For theorists genuinely committed to historical materialism, EUE theory should provide a welcome antidote to mainstream economics.

KEYWORDS

Ecologically unequal exchange; materialism; value

Although ill-informed, Peter Somerville’s (2021) brief critique of ecologically unequal exchange (EUE) theory is welcome, because it candidly illustrates the extent to which traditional Marxist value theory is insufficient in accounting for global inequalities in the 21st century. In his 2½-line abstract, he claims that EUE theory is “confused” and “internally inconsistent,” but he comes nowhere near to substantiating that claim. The confusion is entirely his own, illustrating the conceptual limitations of social scientists mired in the vocabulary of critical political economy dating to 1867.

The only definition of unequal exchange that Somerville is prepared to accept is based on the ancient observation that labourers are paid less money in wages than the products of their labour will fetch on the market. He traces this labour theory of value (LTV) from David Ricardo in 1823 through its transformations in Hobson and Lenin to Emmanuel and Amin in the 1970s. Common to all these approaches (and I assume Somerville would include Marx’s as well) is the definition of exploitation as an unequal exchange (an asymmetric transfer) of labour value between different social groups. True to its origins in 19th century political economy, this conceptualization of unequal exchange is amenable to only one kind of metric: money. As recognized already in Lenin’s notion of a “labour aristocracy,” to understand global exchange flows exclusively in terms of economic values invites questions about the extent to which the Global North’s relatively affluent working classes could be seen as participating in the exploitation of the Global South. This is one of the issues that research on EUE illuminates, but precisely by considering other metrics in addition to expended labour time (dubiously translated into a monetary metric). What Somerville is unable to fathom is that an exclusive focus on flows of “value” is as idealist and myopic as the mainstream economics with which the LTV has always been in dialogue. In limiting itself to considering flows of “value,” the LTV remains as blind to global social-material metabolism as neoclassical economics.

To acknowledge this material aspect of world trade is the whole point of EUE theory, and it is profoundly paradoxical that “historical materialists” should need to be persuaded that this is an important task. Stephen Bunker (1985) attempted to complement the LTV by emphasizing unequal flows of energy, but in theorizing them as “energy values,” he remained constrained by the economic discourse in which he participated. Contrary to Somerville’s narrative, Bunker never used the expression “ecologically unequal exchange,”Footnote1 but his proposition that the unequal structure of world society must be understood in more material terms than through an exclusive focus on flows of “labour value” was pioneering and supremely valid.

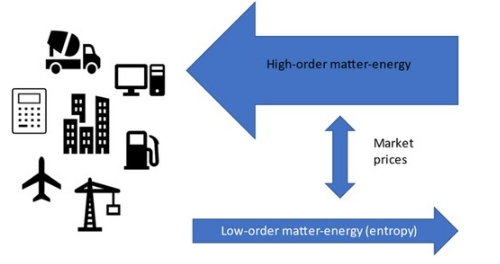

The “problems” that Somerville detects in EUE theory reflect fundamental flaws in his own understanding of global social metabolism. His complaint that it pays too little attention to the exploitation of labour is predictable, given his own conviction that all other metrics are irrelevant. The asymmetric global transfers of embodied labour are an important component of EUE studies, along with asymmetric transfers of other embodied resources such as energy, materials, and land (Dorninger and Hornborg 2015; Dorninger et al. 2021). Regardless of the material substance of what is exchanged in world trade, EUE theory is concerned with the objectively asymmetric biophysical transfers that occur as a result of how commodities are priced on the market. This is as significant whether we are considering the commodity of labour-power or other commodities used as inputs in production processes. Somerville finds that EUE theory lacks “explanatory force,” as if the asymmetric flows of resources to 19th century Britain or the Global North today were irrelevant to understanding growth and accumulation. He does not grasp how asymmetric transfers could be referred to as “exchanges,” oblivious of the observation that those transfers are inherent (but veiled) in global market exchange. He asks Bunker “what is the energy exchanged for?” The answer, of course, are the commodities exported from cores to peripheries. Apparently unaware of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, Somerville does not realize that the finished products must represent less available energy than the resources that are dissipated in producing them (Figure 1). He inexplicably wonders how a slowing down of such energy flows would benefit the South or disadvantage the North, which is like asking what use there would be in starving a parasite to save its host.

Figure 1. The necessary connection between the growth of “technomass” and physically unequal exchange. Source: prepared by author.

Somerville’s incapacity to apply a transdisciplinary, socio-metabolic perspective on world society is particularly evident in his assertion that environmental factors are “external” to exchange relations. He finds it confusing to think of world trade in terms of material, biophysical resources “rather than in terms of exchange value.” Is his agreement with neoclassical economists all that complete? His attempts to apply an LTV template to the global phenomenon of EUE demonstrate the limitations of such an approach, as when he asserts that unequal exchange “occurs only if the value of the transferred resources is more than what was paid to buy them.” This assertion implies that resources have objective “values” that may exceed their price. This is a standard position in both LTV and energy theories of value (Lonergan 1988; Foster and Holleman 2014) but raises questions to which no satisfying answers have been given: Who is to determine those objective values, and in what other metric than money could they possibly be measured? Economic value is not inherent in a resource but attributed to it by market actors (Röpke 2021). The notion of an objective value is thus a contradiction in terms. A conclusion of EUE theory is that global differentials in the attribution of economic value to labour-power and other embodied resources exchanged on the world market lead inexorably to asymmetric resource flows. This is in agreement with the empirical results of Emmanuel’s (1972) foundational study, but suggests two important theoretical adjustments: what is unequally exchanged between nations is embodied labour, rather than “labour value,” and labour is only one of the several types of unequally transferred resources that should be acknowledged. Contrary to Somerville’s strange conclusion that EUE theory ignores “the harms caused by the production and distribution of the transferred resources,” it is precisely by considering flows of other resources in addition to labour that EUE theory does illuminate such harms.

Somerville suggests that “it is possible to have an equal exchange between labor-power and wages while at the same time the worker produces more value than the value of their wages.” I fail to see how this sentence could possibly make sense. I was under the impression that the LTV would approach unequal exchange precisely as the difference between the exchange-values of the products and the wages of the labour that went into producing them. Furthermore, of course, there is the problem of defining the “objective” value of labour-power in terms of what is required to reproduce it: are we talking minimum energy requirements or average living-standards (in the United States or Mozambique)? Such theoretical constructions are not very useful. Remarkably, also, Somerville appears to think that his worries about how an emphasis on wage differentials might “weaken the prospects for international worker solidarity” serve as an argument against EUE theory. This is a political perspective, which we should expect Somerville to distinguish from analytical argument.

In conclusion, Somerville finds that EUE research obscures more than it reveals. It will come as no surprise that I am of the diametrically opposite opinion. EUE theory reveals the material inequalities that mainstream economics and even the LTV of heterodox economics obscure. Calculating the net imports of embodied biophysical resources to core areas of the world-system reveals, for instance, that an economically average American family with four children in 2007 had the equivalent of two full-time servants working for it outside the nation’s borders (Dorninger and Hornborg 2015). In the same year, an economically average Japanese family with four children required the produce of six hectares of eco-productive land outside the country (Dorninger and Hornborg 2015). In 2021, the ecological footprint of the average American is over 8 hectares, while the average footprint in Mozambique is 0.87 hectares. Are average American wage-workers as exploited as average Africans, while they may use ten times the amount of global resources?

Ultimately, the point of illuminating the material asymmetries of world trade is not just about exposing the idealist myopia of mainstream economics. It is to account for the highly uneven accumulation of physical infrastructure that is visible in satellite images of night-time lights. When this accumulation of “technomass” took off in 19th century Britain, Marx celebrated the rising technological productivity of British workers. Little did he consider that, in terms of social-material metabolism, this enhancement of British productivity (the “Industrial Revolution”) largely occurred at the expense of people and landscapes in the peripheries of the British Empire. This is what EUE theory can illuminate. A century and a half after the establishment of neoclassical economic theory in Victorian Britain, mainstream discourse still blatantly ignores the materiality of world trade. Will heterodox economics continue to align itself with this idealist concern with flows of “value,” or will it finally deserve to call itself “materialism?”

From: Capitalism Nature Socialism 2022 33 (2)

Link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10455752.2022.2037675?src=recsys.